This means this half term could be the first time your child encounters a disabled person in real life.

TV and films do a pretty good job of including disabled presenters and storylines (think CBeebies and Cerrie Burnell; Lucy Martin and the weather; Finding Nemo, Finding Dory) – the list, while not quite endless, is growing. Nonetheless for young children in particular, encountering a disabled person in the flesh can give rise to their natural curiosity and some fairly blunt questions. These are often asked with a piercing and hitherto unheard clarity, leaving parents embarrassed and unsure how to answer.

Here then are a few thoughts on how to talk to your child about disability and banish that sinking feeling.

What‘s the right age to talk to your child about disability? Should you wait until they ask you questions, or find a quiet moment to introduce the topic with your serious face on?

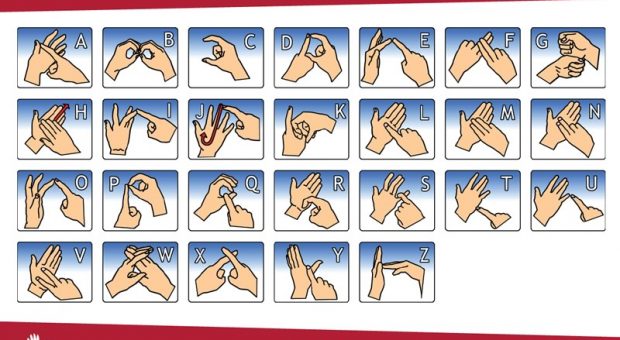

The fact is, your child is learning about the world long before they are able to talk about it, and that includes how disabled people are viewed and treated. As a parent you can introduce them to positive images of disability through the books you read to them (Child’s Play specialise in diversity publications), the toys you buy them (see #ToyLikeMe), the experiences you give them and, as they get older, the language you use.

Once your child begins to ask questions respond promptly and without information overload. If your child asks “why is that boy in a wheelchair?” don’t give a run-down of all the conditions and circumstances which might lead to using a wheelchair. “Because his legs work differently to ours, so he uses a wheelchair to move around” will suffice.

In addition, if your child shows curiosity about a disabled classmate, it’s an opportunity to talk about practical ways in which they could help, e.g. ensuring that they don’t leave things lying where they could become an obstacle or remembering to ask before stroking a guide dog. If possible, also ask the child’s parents if there is anything in particular they’d like you to say.

If you don’t know the answer to a question, say so. Resist comments like “Aren’t they brave?” or “Don’t stare” which perpetuate the idea that disability is something to be avoided and that disabled people are in some way “other”, abnormal or unusual.

Most people with disabilities understand that young children’s curiosity has no filter, many will be unoffended by direct questioning and will answer questions if they’re asked respectfully. You’re already teaching your child to have consideration for other people’s feelings, and by enabling them to meet a wide range of people you’re helping them to accept individual differences, which is good for everyone!

By: Sophie Ballinger

By: Sophie Ballinger